Jonathan Kaiman in Beijing

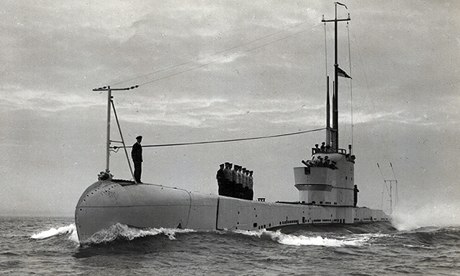

HMS Poseidon, which was a state-of-the-art submarine when the Royal Navy launched it in 1929 but sank only two years later off Shandong province

When the British submarine HMS Poseidon sank off China's east coast 82 years ago after colliding with a cargo ship, the dramatic underwater escape by five of its crew members made headlines around the world.

But the episode was soon overshadowed by the communist insurgency already raging on the mainland, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and eventually the outbreak of the second world war.

The world moved on, the wreck of the Poseidon lay 30 metres beneath the sea, lost to history.

Until now.

Until now.

A new book reveals that China secretly salvaged the submarine in 1972, perhaps to abet its then-incipient nuclear submarine programme.

Steven Schwankert, an American author and diving-company owner in Beijing, spent six years obsessively piecing together the submarine's story; his book about the experience, Poseidon: China's Secret Salvage of Britain's Lost Submarine, was released this month.

"When you start something like this, you say I'm going to start at point A and end at point B. Then suddenly you realise that point B doesn't exist, so you have to go to point C," said Schwankert.

Steven Schwankert, an American author and diving-company owner in Beijing, spent six years obsessively piecing together the submarine's story; his book about the experience, Poseidon: China's Secret Salvage of Britain's Lost Submarine, was released this month.

"When you start something like this, you say I'm going to start at point A and end at point B. Then suddenly you realise that point B doesn't exist, so you have to go to point C," said Schwankert.

"The challenge wasn't to find the submarine per se, but to prove that the story of the salvage was correct."

Although Schwankert never found the exact reasons behind the salvage, he has a few guesses: perhaps fishing nets were getting caught on its periscope, or China, then deep into the Cultural Revolution, simply needed the scrap metal.

Although Schwankert never found the exact reasons behind the salvage, he has a few guesses: perhaps fishing nets were getting caught on its periscope, or China, then deep into the Cultural Revolution, simply needed the scrap metal.

Or perhaps the Chinese navy's underwater special forces salvaged the wreck as practice.

"In 1972, China's nuclear submarine programme was just getting started," he said.

"In 1972, China's nuclear submarine programme was just getting started," he said.

"If you have that kind of a programme, one of the first things you need to know is: if we lose this thing, can we recover it?"

On 9 June 1931, HMS Poseidon – one of the Royal Navy's state-of-the-art submarines – was conducting routine drills near a leased British navy base off the coast of Shandong province when it collided with a Chinese cargo ship, tearing a hole in its starboard side.

Although 31 of its crew members managed to scramble off before the submarine went down, 26 were trapped on board.

On 9 June 1931, HMS Poseidon – one of the Royal Navy's state-of-the-art submarines – was conducting routine drills near a leased British navy base off the coast of Shandong province when it collided with a Chinese cargo ship, tearing a hole in its starboard side.

Although 31 of its crew members managed to scramble off before the submarine went down, 26 were trapped on board.

Eight were stuck in the submarine's torpedo room, and over the next hour, they used a predecessor to modern scuba equipment to reach the surface – the first time submariners had used breathing apparatus to escape a stricken boat; until then, crew members had been taught to simply wait for help.

Five of the men survived.

The incident made the front page of the New York Times, inspired a feature film, and changed maritime practice – the Royal Navy began adding escape chambers to submarines and expanded its research into treatment of decompression.

Schwankert first learned about the Poseidon while planning an underwater expedition to wrecks from the 1884-85 Sino-Japanese war.

He was fascinated by the vague descriptions of the Poseidon and sepia photographs that he found online, and set out to learn more, believing that the wreck remained on the seabed near Weihai, a port city in Shandong province.

The incident made the front page of the New York Times, inspired a feature film, and changed maritime practice – the Royal Navy began adding escape chambers to submarines and expanded its research into treatment of decompression.

Schwankert first learned about the Poseidon while planning an underwater expedition to wrecks from the 1884-85 Sino-Japanese war.

He was fascinated by the vague descriptions of the Poseidon and sepia photographs that he found online, and set out to learn more, believing that the wreck remained on the seabed near Weihai, a port city in Shandong province.

After a year of investigating, he began to have his doubts.

By combing through Chinese-language Google search results, Schwankert began to find online articles mentioning the salvage, including one on the website of the Shanghai salvage bureau.

By combing through Chinese-language Google search results, Schwankert began to find online articles mentioning the salvage, including one on the website of the Shanghai salvage bureau.

On one online forum, he found testimony from a man who allegedly saw the wreck being hauled on to the shore while swimming in the ocean.

China's foreign ministry confirmed later that the submarine had been salvaged, but refused to provide any details.

China's foreign ministry confirmed later that the submarine had been salvaged, but refused to provide any details.

"Some people have suggested that I go out there and look at the site anyway. I said how can you do that? How can you prove a negative?" Schwankert said.

"Every indication is that they brought up the whole thing."

0 comments:

Post a Comment