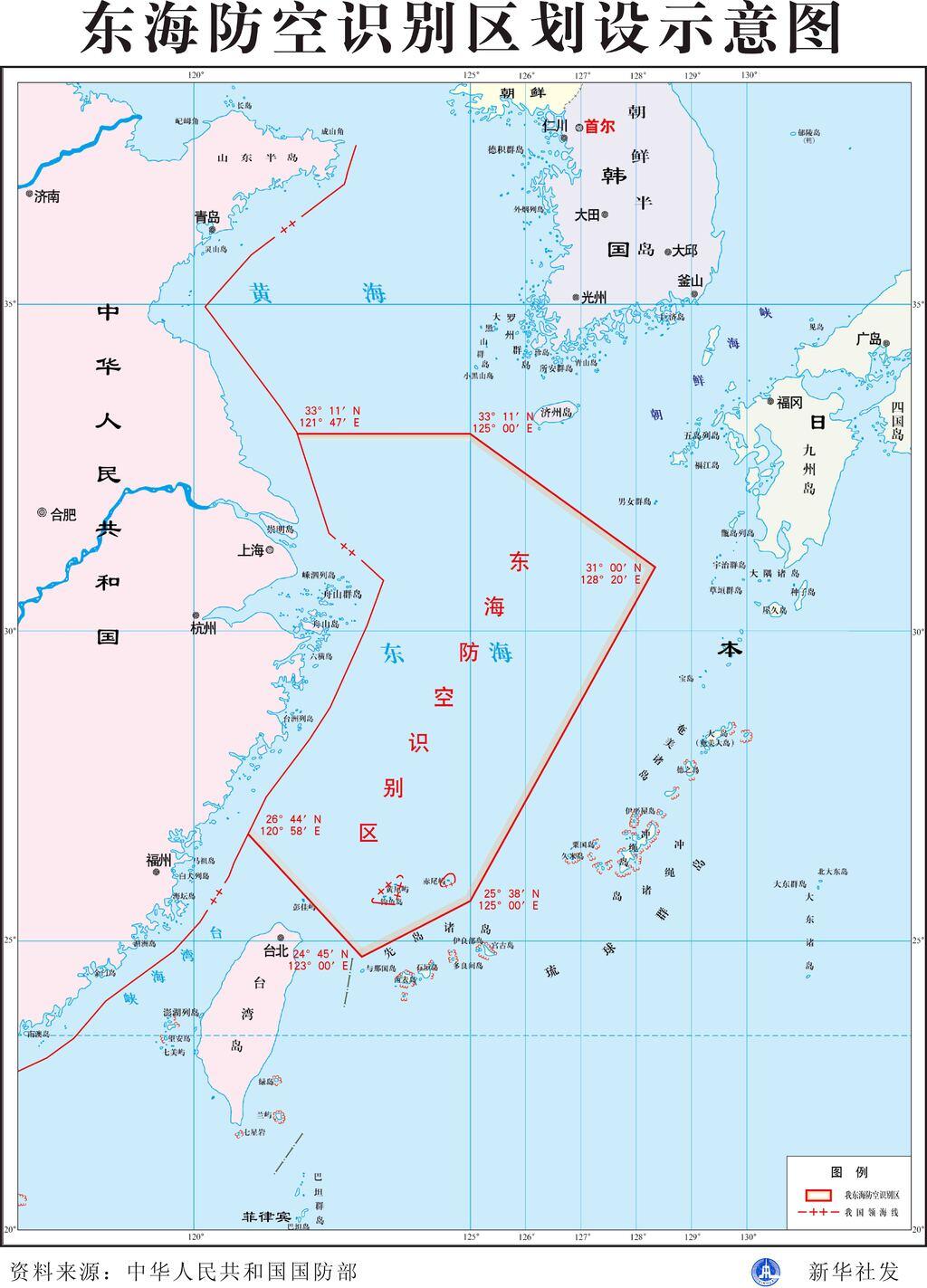

China’s proclamation of a new “air defense identification zone,” an obscure aviation term that became the catalyst for escalating military tensions with Japan and the United States this week, has thrown a broader spotlight on the control of international airspace, an issue that has created confusion, and danger, in other places affected by territorial disputes.

Who has the right to fly where has been a historical irritant in relations between China and Vietnam, Panama and Colombia, Japan and Russia, to name a few examples.

Aviation experts say airspace-control arguments are perhaps most acute in Cyprus, the divided Mediterranean island, where rival air traffic controllers on the Greek and Turkish sides do not communicate with each other and can give conflicting flight information to pilots, elevating the risk of collisions.

No international treaties or agreements define the size or the rules of air defense identification zones, known by their initials, A.D.I.Z.

The zones, which originated early in World War II, have been established by more than a dozen countries with maritime borders, most notably the United States and Canada.

The B-52 message

The United States was also responsible for defining the zones claimed by Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, a legacy of the American military role played in the region since the Cold War, and an underlying source of resentment in China that perhaps helps to explain why it has asserted its own zone.

Managed by domestic military and civilian authorities, the zones are much bigger than the internationally recognized boundaries of the countries that proclaim them.

While not legally binding, they require that aircraft intending to enter the zones first provide identification and location information to determine whether they are a threat to national security.

Aircraft that fail to comply may be regarded as hostile, potentially leading to their being forced to land or shot down.

Civilian aviation officials said Wednesday that China’s new zone was just another fact of life international commercial airlines must now take into account in their flight plans and scheduling.

“There have been no delays, disruptions or anything that would impact the traveling public,” said Perry Flint, a spokesman in Washington for the International Air Transport Association, a trade group.

“We continue to monitor the situation closely.”

Others said, however, that China’s new zone was different in some important respects — the most obvious being that it overlaps with Japan’s in an area where both claim sovereignty to the Senkaku islands.

Aircraft traversing that airspace could face a confusing situation.

“The question here is, file the intent with which nation?” Robert Mann, an aviation consultant, said.

“Seems the jury is out about filing to one, the other, or both. It won’t really be an issue until someone’s aircraft is intercepted. Hopefully not.”

The Chinese also imposed requirements that other countries do not, notably that all aircraft — even those that are not flying to a China destination but are simply passing through — provide identification and flight plans.

Secretary of State John Kerry made a point of emphasizing that distinction in his criticism of China’s new zone on Saturday.

“The United States does not apply its A.D.I.Z. procedures to foreign aircraft not intending to enter U.S. national airspace,” he said.

China provided no advance warning of its new zone to the International Civil Aviation Organization, a United Nations specialized agency, based in Montreal, that sets standards and regulations necessary for aviation safety and security.

Anthony Philbin, a spokesman, said in an emailed response to a query that “China was not required to contact I.C.A.O. on this matter and it therefore did not provide us with any notice.”

Some airlines have begun filing plans with China.

Singapore Airlines, which does route flights over the disputed airspace, files its plans with the Japanese authorities but said that since Monday it had “been keeping Chinese authorities informed” of flights through the area, according to a spokesman.

It is rare that commercial airlines become hostages to political disputes, but there are precedents.

In 1983, Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was shot down by a Soviet military jet after flying through a prohibited zone.

All 269 people on board died.

0 comments:

Post a Comment