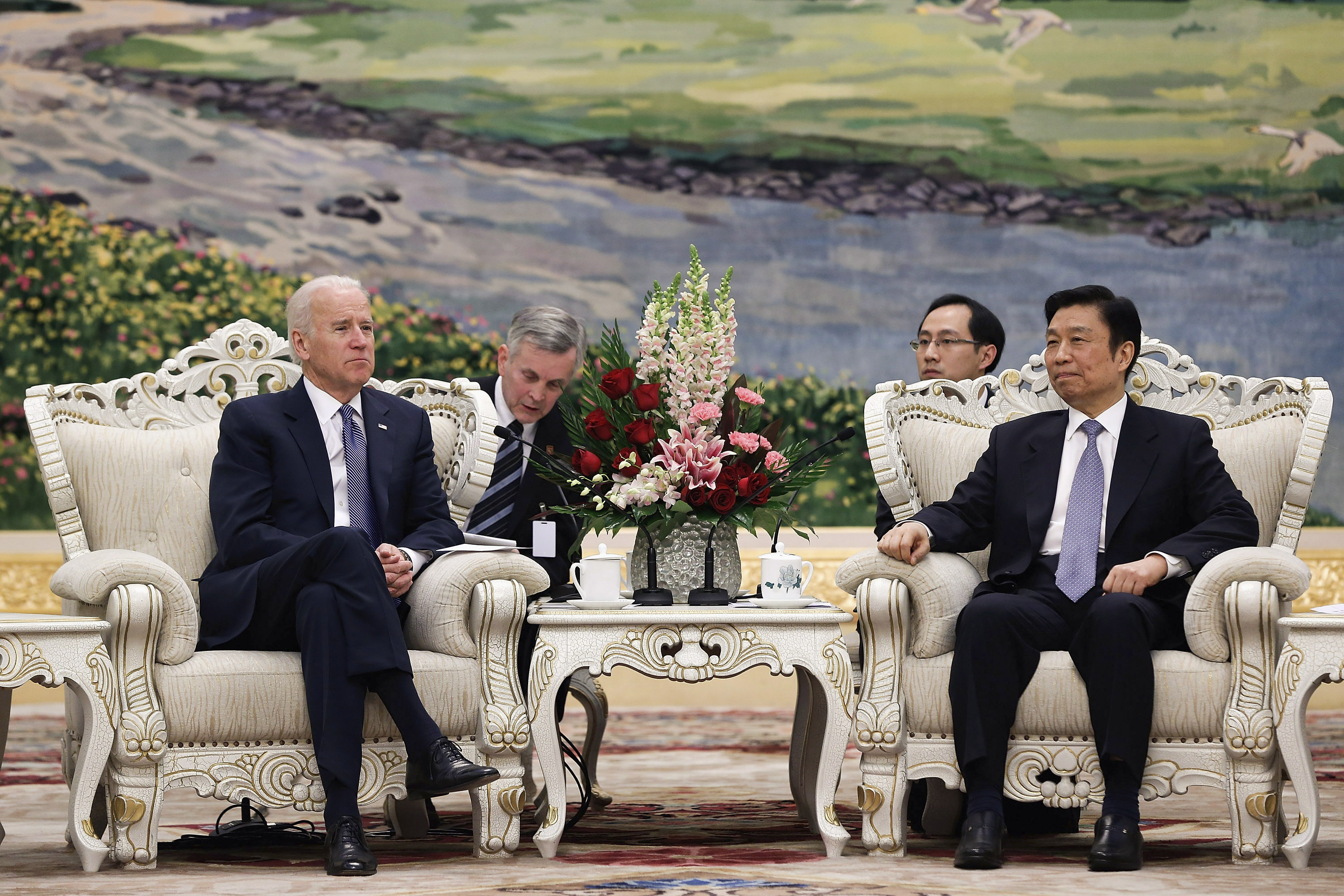

Vice President Biden cooled tensions in his talks with Chinese leaders, but many in Asia and the U.S. now question whether that’s the right course.

By Leslie H. Gelb

“We’re being too soft on China”—such are the increasingly audible whispers of an ever mounting number of China’s neighbors and U.S. foreign policy experts.

They are still mostly whispering because of the enormity of such a change in policy direction. And they certainly don’t wish to trigger crises.

But they do feel that the U.S. needs to get tougher with Beijing.

To them, China unilaterally asserts its rights and demands, doesn’t budge, wears everyone down, waits and waits until everyone shrugs and goes along.

Vice President Joe Biden handled his visit with Chinese rulers in the traditional manner: that is, he was strong in defending American values and concerns, but always far short of confrontation. And Chinese leaders mistook his care as weakness.

Perhaps they’ve seen this as weakness all along.

Or as Winston Lord, a former ambassador to China, put it: “The Chinese do not shy from provocation and count on eventual foreign forebearance. It is time to parry this pattern and be willing to risk some dustups."

Such commentary on the Biden visit did not rise above murmurs here and there.

Or as Winston Lord, a former ambassador to China, put it: “The Chinese do not shy from provocation and count on eventual foreign forebearance. It is time to parry this pattern and be willing to risk some dustups."

Such commentary on the Biden visit did not rise above murmurs here and there.

Those pushing for a tougher line toward China realize such a policy shift takes time, and can’t be decided upon in the space of a week or so, the time it took to digest China’s imposition of its new Air Defense Identification Zone or ADIZ over the Japanese islands in the East China Sea.

If Washington is to adopt a tougher stance toward Beijing, it needs a lot of methodical calculation.

And U.S. diplomats would have to ensure beforehand that Asian nations would follow suit, so that Washington did not string itself out alone.

The Obama administration is not near such a policy departure.

And so, Biden deftly carried out his prescribed paces, perhaps disturbing no one greatly beyond the Japanese.

Japan is less and less inclined to let Beijing push it around. In this regard, they’re out in front of the U.S. government, but they are not alone.

Many Asian and American policy experts were quite unhappy about China’s new ADIZ—and with the Obama administration’s quick acceptance of China’s right to do so.

Washington alerted U.S. commercial airlines (not military aircraft) to comply in order to avoid mishap.

There was good reason, however, not to do so.

Washington acknowledges the right to establish ADIZ’s.

But by U.S. policy, commercial aircraft flying through such zones need identify themselves only if they intend to enter Chinese airspace.

More to the point, Beijing’s new ADIZ was announced without warning or consultation over an unusually large area, and an area that was in hot dispute with Japan.

Japan and South Korea did not go along with the new China ADIZ, and the White House or State Department should have coordinated the U.S. response with these and other countries.

It’s not a stretch to assume that Chinese leaders took the U.S. response as caving in to their excessive demands.

It’s not a stretch to assume that Chinese leaders took the U.S. response as caving in to their excessive demands.

Tokyo certainly came to that precise conclusion.

Apparently, Biden made no hard line effort to walk this cat back in Beijing.

Instead, he seems to have asked his Chinese counterparts simply not to “enforce” the new ADIZ rules.

Later in his Asia trip, in South Korea, the U.S. position appeared to have hardened, with a U.S. briefer saying that the U.S. and others did not accept China’s ADIZ.

In the familiar refrain of diplomats, only time will tell.

The new ADIZ is only the latest in a long line of lamentations about Chinese treatment of American interests.

The new ADIZ is only the latest in a long line of lamentations about Chinese treatment of American interests.

There’s the cyberwarfare against U.S. defense industries.

There’s Chinese flagrant violation of intellectual property rights.

There’s the near total resistance to opening up Chinese internal markets to fair competition and to letting outsiders own a majority share of businesses.

There’s strong resistance to accepting the WTO trade rules on the grounds that though China is an economic juggernaut, it’s really a “developing country” and thus not subject to the same rules as America, Japan, Germany, et al.

There’s the constant intimidation of American journalists and news organizations.

Biden did note the latter publicly as a matter of American values.

Did Beijing even notice?

Asian nations certainly feel Beijing has been pushing them around, increasingly.

That’s why they pressured the Obama team to “pivot” or “rebalance” its policy and resources from Europe and the Mideast to Asia and the Pacific, a course already favored by the Obama team.

To be sure, and at the same, Asian leaders worry about being too closely associated with a tougher U.S. They want Americans to be tougher, but they don’t want Beijing to blame them for it. (It’s the old story with America’s friends and allies.)

Then, there’s the question that troubles all serious policy makers—exactly what leverage does Washington actually hold over Beijing?

Then, there’s the question that troubles all serious policy makers—exactly what leverage does Washington actually hold over Beijing?

No military expert dreams of challenging China’s military power on the Asian mainland. The manpower gap is insurmountable.

But at sea and on the coastlands, the U.S. Navy and Air Force remain clearly superior. China’s knows all this.

But the last thing anyone desires is a military confrontation.

There’s no telling where this would lead.

By the same token, however, China can’t simply be allowed to make its own rules at sea by asserting its unilateral rights and dispatching ships and fighter planes to enforce them.

So far, China has been doing the asserting in both the East and South China seas, resource rich areas, much to the dismay of the Philippines, Vietnam, South Korea, and Japan.

But the real leverage between the U.S. and China comes down to economic horsepower.

But the real leverage between the U.S. and China comes down to economic horsepower.

However much military strength is needed, and it is, policy makers understand full well that power in the region stems from domestic economic strength and vitality, plus trade and investment power.

China’s economy still marches upward and has already surpassed Japan’s.

The American economy is limping along.

Congress hasn’t passed a budget in six years. It regularly brings the nation to debt default.

It won’t increase funds for physical and intellectual infrastructure, where America is clearly falling behind.

If China or anyone else, for that matter, is going to pay attention to America’s wishes and demands, Congress will have to stop acting like a Banana Republic.

The Tea Baggers say they want a strong America; they’re destroying it.

Ambassador Lord provided this perspective: “We need a firmer posture toward Beijing which means getting our domestic political and economic acts together, investing in the future; giving our Asian rebalancing more heft by successfully concluding the critical Pacific trade pact; and helping to reconcile our two most important Asian allies, Japan and South Korea."

Stapleton Roy, another former U.S. ambassador to China, who opposes the tougher line, put his case rather pithily: “You talk about getting tough on China,” he chuckled, “We first should get tough on ourselves.”

Ambassador Lord provided this perspective: “We need a firmer posture toward Beijing which means getting our domestic political and economic acts together, investing in the future; giving our Asian rebalancing more heft by successfully concluding the critical Pacific trade pact; and helping to reconcile our two most important Asian allies, Japan and South Korea."

Stapleton Roy, another former U.S. ambassador to China, who opposes the tougher line, put his case rather pithily: “You talk about getting tough on China,” he chuckled, “We first should get tough on ourselves.”